The Mandela of Malayan journalism

More than anyone else in Malaysia and Singapore, Said Zahari’s name must surely be immortalised as symbolising the struggle for press freedom. The defining moment was, of course, the Utusan Melayu strike of 1961, when he led his colleagues to resist the newspaper’s takeover by interests tied to Umno, the ruling party then and now.

The strike was remarkable for many reasons; two deserve special mention. First, it involved Malay workers unlike most labour struggles historically associated with ethnic Chinese and Indian workers.

Second, the strike was not primarily over workers’ welfare, but instead tried to resist the takeover and transformation of the previously independent Malay-language newspaper into a ruling party tool.

The strike lasted over 100 days, marking the end of the honeymoon of organised labour with the post-colonial government. The strike finally ended after Said was banished from re-entering Malaya by Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman.

Dark clouds over Singapore

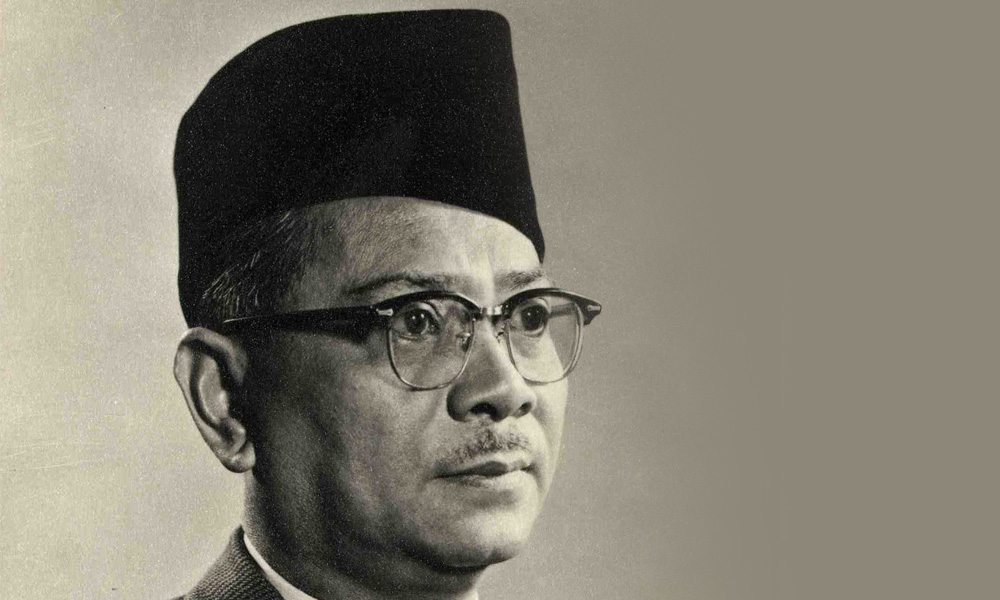

Said Zahari (photo above, far right) then became one of the most prominent political prisoners of Lee Kuan Yew’s government in Singapore. He was arrested together with over 100 others in ‘Operation Cold Store’ in early February 1963, and was incarcerated without trial for 17 years.

His Malaysian wife, Salamah, suffered much hardship supporting their family, including their youngest daughter Norlinda, born after his arrest. Said’s poems written in prison were smuggled out, compiled, edited and published in the early 1970s by his closest friend, poet Usman Awang.

He was assisted by former senator, Professor Syed Husin Ali, himself a political detainee for six years following the 1974 student-led Baling protests. Fine English language translations were done by another dear friend, the late Dr MK Rajakumar, last chairperson of the Labour Party of Selangor, also detained without trial in the mid-1960s.

Inspiration

Said’s poems and Usman’s own ‘Salute to Said Zahari’ were read and recited by thousands of students, activists and sympathisers in Malaysia and abroad for years. These encouraged struggles by countless others, inspired by his selfless and resolute determination despite his ordeal.

Said’s memoirs, published a quarter-century ago, recount how he came to make selfless sacrifices for a better, more just and democratic post-colonial nation with no thought of personal gain.

They also reveal Said for the outstanding human being he was. Affable, generous, trusting, loving and humble, he was also principled, uncompromising and defiant when it mattered.

A little younger than Kuan Yew and Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Said’s memoirs were not only political but also personal. He candidly shared reminiscences of a bygone era, without the cosmetic editing ‘great men’ demand of their biographical narratives.

His memoirs tell of growing up, the Japanese Occupation, coming of age, working and family life. He first joined what must surely have been among the most exciting working environments in late colonial Malaya - the Utusan Melayu headquarters in Singapore.

The paper was led by Yusof Ishak, later Singapore’s first president, and A Samad Ismail, the doyen of Malaysian journalism and unofficial patron of the progressive nationalist Malay literary movement, Asas 50.

Region in turmoil

Said was sent north in 1955 to open the Kuala Lumpur office before Merdeka, in time to cover the historic December Baling peace talks. He revealed that Federation of Malaya Chief Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman privately confessed that he never intended for the talks to succeed, but had only agreed to them to secure political advantage.

In 1962, the anti-colonial Parti Rakyat Brunei (PRB) captured all but one of the elected seats for the colonial sultanate’s legislative council in its first - and last - election. After the newly elected legislators were ignored by the colonial authorities, most PRB leaders were detained or exiled after a failed ‘insurrection’.

Less than two months later, in early February 1963, only hours after Said agreed to lead the PRB’s fraternal party in Singapore, the Parti Rakyat Singapura, he was detained under Operation ‘Cold Store’ for 17 years.

Generous spirit

After such an extraordinary life, Said remained modest, but always generous and avuncular in his dealings with all. It says so much of him and so many of his comrades that they came out of their protracted travails with so much of their humanity intact, if not enhanced.

One cannot but marvel at his generosity of spirit, for example, when some who had caused him untold misery sought to redeem themselves with him. One cannot but contrast his magnanimity with the petty vindictiveness which characterises so much of modern political and social life.

Although he said little about the matter, Said tried to compensate his family for his protracted involuntary absence, despite his limited and modest means. This sense of personal guilt must have been very difficult for him to bear.

During his lifetime and beyond, many partook of his love for truth, freedom, humanity and other cherished values, for which we are all eternally grateful. His was truly a life of great sacrifice for principles that continue to move us so many decades later.

Remembering Said

The course of subsequent events suggests that history has clearly come down on Said’s side, namely that of truth. His memoirs reveal a complex and diverse Left, quite unlike the monolithic image promoted by the powers-that-be, lazy scholars, foreign observers and the servile media.

This is evident in his takes on debates and differences among the Left in Singapore, his friendship with Lim Chin Siong (photo above, middle) - the most popular Singapore politician of the time - and others, his criticisms of a leading communist’s dealings with Lee Kuan Yew, and his meeting with Chin Peng, the long-time Communist Party of Malaya secretary-general.

Malaysia, Singapore and indeed the region will forever owe him and his comrades a debt that can never be repaid. It is an honour to salute Said Zahari, and in doing so, to be inspired by his life and example.

Photo: (from left) Ahmad Boestamam aka Abdullah Sani (founding president of Parti Rakyat Malaysia), Lim Chin Siong (Singapore's left-wing politician and trade union leader, co-founder of People's Action Party), and Said Zahari.

JOMO KWAME SUNDARAM is Fellow, Academy of Science, Malaysia, and Emeritus Professor, University of Malaya. He was Founder-Chair, International Development Economics Associates (IDEAs), UN Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development (2005-2015) and received the 2007 Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

✍ Credit given to the original owner of this post : ☕ Malaysians Must Know the TRUTH

🌐 Hit This Link To Find Out More On Their Articles...🏄🏻♀️ Enjoy Surfing!

Post a Comment