Improving disclosure for election costs

Recently, we came to know the full cost of the Sabah state election - RM130 million - which was released in a written parliamentary reply earlier this year. This written parliamentary reply warrants an important discussion about the election expenditure.

Elections are costly affairs and due to an attempted political coup in Sabah amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, the Malaysian government had to expend RM130 million for one state election. In this article, we will examine the rationale behind election costs and how the country’s election expenditure can be improved.

Fortunately, in this written parliamentary reply, the brief itemised expenditure of the Sabah state election was displayed. Out of the RM130 million, around RM69 million was spent on rentals and around RM39 million was spent on “professional services, other acquired services and hospitality”.

In Tindak Malaysia’s existing research of past Election Commission’s (EC) election reports from 1959 to 2004, the presence of itemised election expenditure was only reported for the 1964 Malaysian general election, the 1967 Sabah state election, the 1995 Malaysian general election and the 1999 Malaysian general election.

With this limited information available over the past decades, we were able to shed some light on election expenditure and evolving costs.

In the 1960s election reports produced by the EC, they used to have a few pages to describe election costs. This included the honoraria amount for various tiers of polling staff. Since the 1970s, information on honoraria or salaries for election workers were no longer shown in the election reports.

In our study, minor cost items in a given election would be small repairs, food and drinks, overtime allowances and travel and associated expenses (each of the items constitutes less than 10 percent of the total cost). Major cost items would be rentals (could be more than 40 percent of the budget) and professional services and other associated services (could be more than 30 percent of the budget).

To make sense of these costs, we also need to delve into the reasons why election costs are increasing. From our research of election reports of the past and our experience as Pemerhati (Election Observers), the following are the reasons why election costs go up:

1. Increasing size of the electorate, which results in:

a. More polling districts (which defines where you vote)

b. More polling stations

c. More polling streams (saluran in Malay)

d. More polling staff

2. Increase in the number of parliamentary and State Legislative Assembly seats

3. Increase in printing cost

a. Rising cost for ballot papers and other documents

4. Increase in petrol price:

a. Since 1999, the EC made polling a one-day affair for Sabah and Sarawak

b. This resulted in an increase in rentals of helicopters, four-wheel drives and boats

5. Increase in allowances for polling staff

6. Printing new editions of election laws

7. Increase in purchasing cost for election materials (i.e. introduction of transparent ballot boxes, adaption to Covid-19 requirements)

8. Overall management of elections under the Covid-19 pandemic

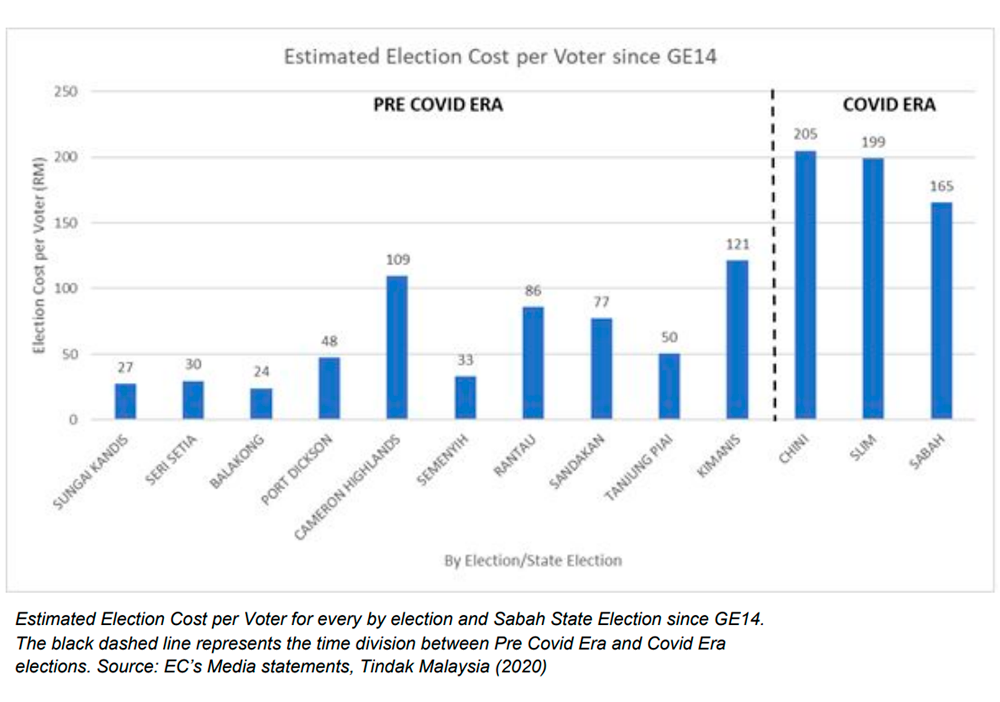

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the average election cost per voter was less than RM100 for every by-election with the exception of the one for Cameron Highlands. For the Cameron Highlands by-election of 2019, helicopters were rented to bring the ballots in from the remote parts of Jelai to the final counting centre.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of polling streams was increased under the direction of the reformist EC. After GE14, the number of voters per polling stream was reduced from 750 to 600. This reduction of the number of voters per polling stream resulted in an increase of additional streams (where an additional polling stream would require employing four to five staff per stream).

For every state constituency and parliamentary by-election after GE14, 20 new polling streams were added to a constituency. Moreover, the reformist EC, under the then leadership of Azhar Azizan Harun, made great strides in improving voter experience.

This translated into infrastructural improvements for polling stations and the rental of golf buggies so that every voter (including individuals with a disability and the elderly) was able to access polling stations with ease. During the Kimanis by-election in 2020, EC invested an allocation from the election budget to upgrade pavements at some schools (that served as polling stations) to ease voter access.

Furthermore, the EC invested additional monies in posting voting cards to every voter for the recent by-elections so that the voters knew where to vote. We hope this disincentivises voters from entertaining political party 'hot booths' (pondok panas) that are engaging in illegal campaigning on election day.

Expensive business

When the Covid-19 pandemic struck the country, the EC had to amend polling procedures to accommodate elections under these extraordinary circumstances. One of the tangible changes was the reduction of voters per polling stream and this resulted in increased polling streams.

Secondly, additional procedures to mitigate Covid-19, such as the presence of hand sanitiser and usage of gloves by polling staff, were added to the polling process. This also included amendments to the election training for polling staff. This can explain the sudden spike in election costs for state-level by-elections, starting with the Chini by-election of 2020.

With all these facts in mind, we have a better appreciation of why elections are an expensive business in Malaysia (and also for the rest of the world). Having said that, it is imperative that we explore ways to improve election cost management, both in terms of reporting and cost-saving measures.

We have a few proposals for the EC and our lawmakers for improvements with regard to election expenditure. An important aspect in the conduct of elections is to ensure accountability and transparency of the EC in relation to election costs and expenditure. If one were to look at the EC website, one cannot find any annual report of the EC which explains how the annual budget of the EC is being utilised, nor is the itemised election expenditure provided.

Currently, the EC website at best just provides a very brief explanation via its press releases about the overall budget of conducting a general election or a by-election. Any existing online version of annual reports by the EC (surprisingly, not hosted on the EC’s website) shows very little detail of election costs for a by-election or general election.

It must be mandatory for the EC to produce, in an accessible manner (i.e. via EC’s website), yearly statement accounts with an itemised expenditure of elections conducted. At present, it is already mandatory for yearly statements of accounts to be prepared by the Treasury and for all yearly statements of accounts to be prepared by the state financial authorities for the respective state governments as provided under the Audit Act 1957 and the Financial Procedure Act 1957.

This will ensure not only a more accountable and transparent EC but will also enable the EC to justify any increases in overall election expenditure. Some examples will include the increase in salaries and allowances for polling staff and EC officials. Adoption of the 1960s style of EC reports on election expenditure can be a start.

If a proper itemised expenditure is displayed for public view, the public will have a greater appreciation of the certain high expenditures required for elections. Moreover, they will appreciate the long term gain of the infrastructural improvement made by the EC for polling facilities.

Election costs and expenditure incurred by the EC must be audited. At present, the auditor-general can audit the accounts of the federal government, the 13 state governments, other public authorities and specified bodies. The definition of public authorities does not include the EC. However, according to Section 5(1)(d) of the Audit Act 1957, the auditor-general can examine, inquire into and audit the accounts of any other body under Article 106(2) of the Federal Constitution.

Thirdly, we propose the proper codification of the law where usage of schools and public facilities (premises only) to be free of charge for the EC to use as polling facilities as a way to reduce the EC’s overall costs of conducting elections.

Finally, it is important for the public to appreciate the effort the EC has carried out to improve voter experience and safety under the reformist EC since GE14. We hope our research and real-life experience as observers have shed some light on the high election costs in Malaysia. Some of these costs have laid the foundation of long term infrastructural gains for the given community. However, we also need to stress that greater transparency in election expenditure reporting must be carried out.

As elections are an extremely important element of our democratic system, it is important for the public to know how taxpayer monies are spent on the conduct of by-elections. A transparent and accessible reporting of election expenditure is one of the keys to better elections tomorrow.

DANESH PRAKASH CHACKO is Tindak Malaysia’s director and research analyst at the Jeffrey Sachs Center on Sustainable Development (Sunway University). FORK YOW LEONG is an activist with Tindak Malaysia and specialises in law. - Mkini

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

✍ Credit given to the original owner of this post : ☕ Malaysians Must Know the TRUTH

🌐 Hit This Link To Find Out More On Their Articles...🏄🏻♀️ Enjoy Surfing!

Post a Comment