Rare, vintage photographs depict glory of 1946 KL

Recently a rare opportunity presented itself for the acquisition of a medium-sized cardboard box filled with vintage photographs bearing well-taken family portraits and stunning views of landmarks in Malaya.

Based on the smattering of family correspondences, including several picture postcards sent by a daughter touring the United States in the 1980s, it soon became apparent that the photographic gems once belonged to Omar Muhammad, a teacher who taught at the Seberang Perak Malay School in Alor Star.

While not much is known about Cikgu Omar before World War Two, the images of his family members living in Lorong Wan Mat Saman as well as shots of his school taken after the Japanese Occupation portray him as a dedicated husband, doting father and respected educator.

After bearing witness to the ravages of war, Cikgu Omar picked up his prized Rolleicord camera and began the task of recording Malaya's long and gruelling rebuilding process. He initially covered places closer to home like Kangar and Mata Ayer in Perlis as well as smaller Kedah towns, such as Changloon and Kuala Kedah.

His keen photographic instincts came to the fore when capturing bustling scenes around the Butterworth Ferry Terminal (today Pengkalan Sultan Abdul Halim).

Cikgu Omar was quick to realise that there was room to improve his skills and began setting plans in motion to remedy his perceived weakness. Invaluable assistance from friends and fellow enthusiasts cleared the path for his enrolment in a photography course at a renowned Kuala Lumpur studio.

FULFILLING A DREAM

Together with other fellow participants from Kedah, Cikgu Omar embarked on the journey of a lifetime to fulfil his dream of becoming an accomplished photographer during the 1946 December school holidays.

Based on the large number of images taken during that memorable trip found in the box, it became apparent that Cikgu Omar had his camera at the ready throughout the journey and snapped away at interesting landscapes and eye-catching scenes from his train carriage window.

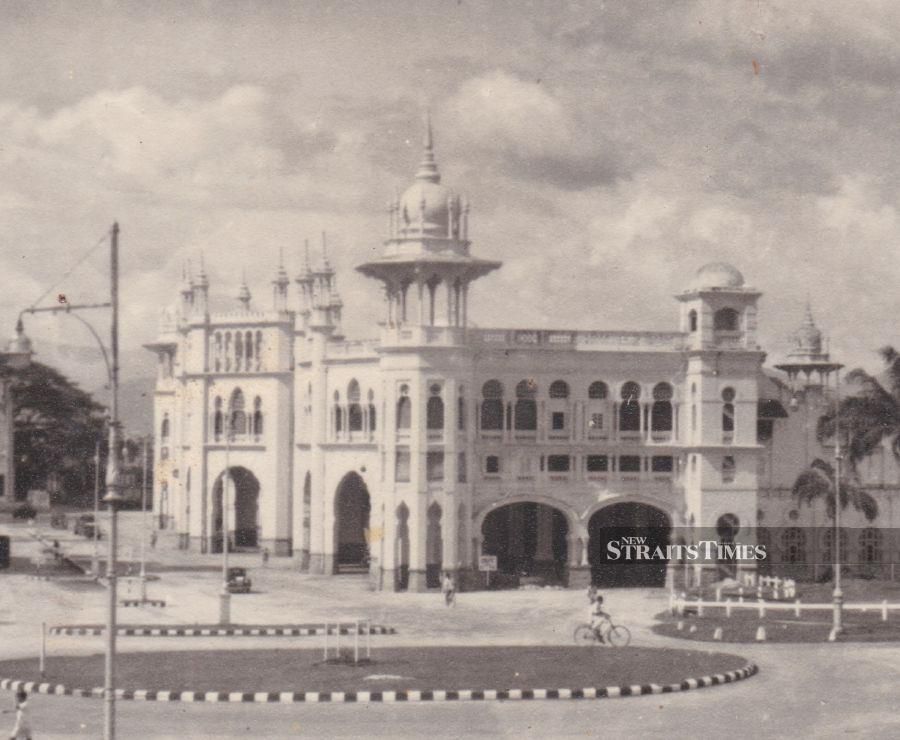

Cikgu Omar hit the ground running upon arrival at the Kuala Lumpur Railway Station. He was fascinated with the ornate building designed by one of the most prolific and talented colonial architects, Arthur Benison Hubback, and decided to put it on film from almost every possible angle.

Since its completion in 1910 and official opening just a year later by Selangor ruler Sultan Alauddin Suleiman Shah, this iconic two-storey structure sporting the Indo-Saracenic architectural style of British India has never failed to capture the imagination of travellers arriving in Kuala Lumpur by train.

This distinctive design surfaced in India around 1870 and reached the height of its popularity at the turn of the 20th century. Its presence in Malaya was attributed largely to Charles Edwin Spooner, who was then the Federated Malay States Railway general manager.

Having worked in Sri Lanka before moving to Kuala Lumpur, Spooner felt that this Muhammadian style was most suited for Muslim-majority Malaya.

TAJ MAHAL OF THE TRAIN WORLD

Dubbed by many as the Taj Mahal of the train world, this attention-arresting, snow-white building is characterised by octagonal towers that flank the central block as well as the gables at both ends of the extended platform canopy.

The towers are topped with dome-capped pavilions, which were first introduced during the reign of the 16th-century Mughal Emperor Akbar.

The allocated budget of $742,980 brought to completion the station, its supporting offices as well as a sixteen-bedroom hotel that provided convenience for passengers seeking accommodation.

Despite being surpassed by KL Sentral as the main railway hub in our nation's capital on April 16, 2001, the station fronting Jalan Sultan Hishamuddin remains, to this very day, one of the grandest colonial buildings in the city.

During his studies in Kuala Lumpur, Cikgu Omar also spent hours exploring various places in the city searching for suitable subject matters to put his new-found knowledge to practice. Among the spots that provided him with a rich hunting ground was Java Street (today Jalan Tun Perak).

Initially settled by Malays and immigrants from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Java Street was a major thoroughfare that formed a physical boundary between the Chinese and Malay areas in early Kuala Lumpur. Due to its proximity to Masjid Jamek, this place was also popular with the Boyanese and Indian Muslim communities.

OLDEST MOSQUE

Built on the sacred ground of an ancient Malay cemetery in 1909, Masjid Jamek is the oldest surviving Muslim place of worship in the city and served as Kuala Lumpur's main mosque until Masjid Negara came into existence in 1965.

Designed by the same architect as the Kuala Lumpur Railway Station, its name is the Malay equivalent of the Arabic word, which means a place people congregate for prayers. In 2017, it was renamed Sultan Abdul Samad Jamek Mosque in honour of the fourth ruler of Selangor.

By the early 20th century, Java Street had developed into a busy commercial area, thanks to its location close to government offices, recreational clubs, cricket grounds and courthouses.

Two decades later, Java Street became so popular that many well-known stores during that period, such as Robinson's, John Little and Whiteaway Laidlaw, decided to have their presence felt there as well.

Founded in Calcutta by Robert Laidlaw in 1882, Whiteaway Laidlaw was a global department store that opened a premier branch in Kuala Lumpur in the 1920s offering imported products that appealed to the European community and wealthy locals.

SHOPPING PARADISE

Together with the other large European businesses, Whiteaway Laidlaw made Christmas in Java Street a grand affair as the entire road was festooned with colourful lights and baubles, giving the British expatriates in Kuala Lumpur a much-welcomed taste of Oxford Street in the tropics.

Java Street's popularity gradually declined in the early 1970s. Stores began giving way to financial institutions. Robinson's was the first of the big three to shutter permanently and its premises were demolished in 1976 to make way for United Asian Bank's headquarters (now Menara UAB).

In 1996, the elevated Ampang Light Rapid Transit (LRT) Line was constructed along the entire stretch of Jalan Tun Perak and the Masjid Jamek LRT Station occupies the location where the Whiteaway Laidlaw Department Store once stood.

Fortunately, some buildings managed to escape the scourge of progress and still form an integral part of the Jalan Tun Perak landscape today. Among them is the Gian Singh Building (1909) and the Oriental Building (1932).

The former, located at the corner of Lebuh Ampang, has a facade featuring a blend of Dutch, English and Islamic influences while the latter sports an Art Deco style.

The Art Deco architectural technique gained popularity and became the preferred choice of many Malayan building owners in major towns like Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Ipoh between the early 1930s and late 1940s.

Construction of the Oriental Building, located at the junction with Jalan Melaka, brought liveliness to the Java Street commercial centre that was suffering due to the aftereffects of the Great Depression.

TALLEST IN KUALA LUMPUR

Touted then as the tallest building in Kuala Lumpur, the Oriental Building was also the largest Art Deco structure in the city besides Central Market (now Pasar Seni). Built by the Oriental Government Security Life Assurance Company, the five-storey structure served as an impressive symbol of Kuala Lumpur's vibrant commercial life.

Also home to Radio Malaya in the 1950s, this triangular-shaped building boasted many state-of-the-art fittings including English tiles on its staircases and passages, while Italian-made ones covered the office floors. The basement was rat-proof and, in case of floods, the doors could be fitted into specially-constructed grooves over the basement windows to make them watertight.

Like many properties which have seen better days, the vacant Oriental Building today stands like a silent sentinel watching over the bustling traffic below. This elegant but yet lonely edifice serves as a gentle reminder of fickle business trends which shift at whim.

As the sun set on Java Street many years ago, it began to shine on neighbouring Jalan Tuanku Abdul Rahman, making it Kuala Lumpur's next Golden Mile.

The existence of several photogr-aphs of the Dusun Tua Hot Springs and Port Swettenham (now Port Klang) in the collection was evidence that Cikgu Omar and his friends had embarked on a brief tour of Selangor upon completing their photography course.

VENTURING BEYOND THE CITY

The former, located in the Ulu Langat District, had been a popular spot for recreation and therapeutic treatment in Selangor since its existence was made public at the turn of the 20th century. Its geothermally-heated groundwater rising from the earth's crust is said to possess medicinal properties to cure skin ailments and improve blood circulation.

Port Swettenham has seen rapid progress since the capital of Selangor shifted from Klang to the more strategically-advantageous Kuala Lumpur in 1880.

With the means of transportation between the two towns confined to horse- or buffalo-drawn wagons and slow boat rides up Sungai Klang to Damansara, plans were put in place two years later by the British Resident of Selangor, Frank Athelstane Swettenham, to build a railway track as a faster alternative route.

Another problem surfaced as soon as the rail link between Kuala Lumpur and Klang was completed in 1890. River navigation was challenging as only small vessels drawing less than four metres of water could dock at the jetty.

NEW PORT FUELS NATION'S GROWTH

This resulted in the selection of a new site near the river mouth. Developed by the Malayan Railway, the new port was opened on Sept 15, 1901, by Swettenham, who was deeply honoured to have it named after him.

Trouble struck in the form of a severe malaria outbreak just after two months of operation, and steps were taken to fill in the surrounding swamps and divert surface water away to effectively destroy all mosquito breeding grounds.

With the malaria threat eradicated, trade grew rapidly and two new berths were added along with other port facilities in 1914. Between the two World Wars, Port Swettenham experienced exponential growth and expansion, peaking in 1940 when tonnage rose to a record of 550,000 tonnes.

Cikgu Omar must have witnessed the ongoing reconstruction of Port Swettenham following the end of the Japanese Occupation during his visit.

While it was not known which mode of transportation Cikgu Omar and his friends took to get back to Alor Star, the fact remains that his photographic prowess improved by leaps and bounds soon after that eventful trip.

He began winning many photography competitions and eventually became an acclaimed photographer in his own right.

Today, many of his important works in private collections as well as at Arkib Negara provide us with invaluable insights into Malayan social life during those formative post-war years. - NST

✍ Credit given to the original owner of this post : ☕ Malaysians Must Know the TRUTH

🌐 Hit This Link To Find Out More On Their Articles...🏄🏻♀️ Enjoy Surfing!

Post a Comment