Time to clean up plastic pollution - and corruption

Rows of abandoned and derelict industrial shop lots loomed up ahead, with dark gaping holes in place of windows and doors. Turning a corner, we saw them – bales and bales of plastic trash neatly stacked up, with creeper vines beginning to hide them from view.

Japanese "Palty" hair dye tubes burst out of an opened jumbo trash bag. An "OMA" bottle from Denmark littered the ground. Some jumbo bags held shredded plastic scraps while others contained nurdles, the tiny pre-production plastic pellets.

We were in Pulau Indah in the Klang district, for which the Malay name translates into “Beautiful Island”. The irony was not lost on us.

A man approached, speaking animatedly into a mobile phone. We jumped into the car and fled. We saw a lone operator still at work, eking out a living amidst the decaying scrap.

We then went to a vacant lot in nearby Telok Panglima Garang where illegal factory operators used to stockpile plastic waste. The wastes have been cleared, but the ground was layered with scraps of microplastics, some clearly charred and melted. There was a fire here.

Next to this land, more unknown materials – some white, some black – were piled high, becoming hills in the landscape.

That was back in January 2020. We were conducting field research for C4 Centre’s report on governance and the imported plastic waste crisis in Malaysia.

China disrupted the global market for recyclable material in 2017 when they announced their ban of 24 types of solid waste imports effective January 2018. This list expanded to 32 types of wastes in 2019. Waste exporters were sent scrambling for new markets, with many landing in Malaysia.

The main reason given for China’s ban was that the imported wastes were causing too much pollution. Since 1992, 45 percent of all plastic waste generated globally had been exported to China. Too much hazardous waste had been smuggled in alongside recyclable materials.

China had finally had enough.

Effect on local communities

The global upheaval in the waste trade had a severe impact on local communities living around our ports, notably Port Klang and Penang Port.

“There were many illegal operators here,” said resident-turned-activist Pua Lay Peng, referring to Pulau Indah, where Westport is situated.

“In 2018 and 2019, they not only sorted plastic waste, but some also burned or dumped the plastics that cannot be recycled.”

Pua was among the first who alerted the authorities about illegal plastic waste recycling around her village in Jenjarom, a town 6km from Telok Panglima Garang. The air pollution was making the people around her fall sick. But her letter and complaints went unheeded until the federal government changed hands in May 2018.

Her efforts with the Kuala Langat Environmental Action Group, and those of similar groups in Klang and Sungai Petani, finally kicked off a nationwide crackdown on illegal plastic waste operations from mid-2018 onwards.

Last Saturday, the black hill sighted in Telok Panglima Garang in 2020 went up in flames, and a deep-seated fire has been engulfing the area for days. The material piled high in the open was reportedly imported scrap tyres.

Like China, Malaysia is now reeling from pollution caused by other countries’ wastes. As with Jenjarom and Klang, Sungai Petani which is conveniently situated not far from the North Butterworth Container Terminal has borne the brunt of China’s waste ban.

Several plastic recycling facilities have caught fire, in January, June and November 2020 among others, releasing enormous plumes of cancer-causing toxic chemicals like dioxins, furans, mercury, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) into the air as plastic stockpiles went up in flames.

This year, the foul smell of burning continues in Sungai Petani. In recent weeks, while quarantined in their homes, residents began complaining of acrid smells again, sharing images of heavy smog on social media.

Numerous complaints have been lodged but the air pollution persists, highlighting the difficulties of enforcement efforts. This is particularly worrying now as research shows that exposure to long-term air pollution increases one’s risk of death from Covid-19.

"Dr Tneoh", a resident of Sungai Petani, reminisced, "We used to cycle around the neighbourhood every morning. Since the plastic waste came to Sungai Petani, many mornings have been shrouded in smoke. We now need to go further away for cycling.”

“In 2019, we were sometimes awakened around 3am and 4am because of the strong bad smell."

As a general practitioner with his own clinic, Tneoh also noted a rise in respiratory illnesses among his patients that year.

The importance of enforcement

Several officers interviewed by C4 Centre expressed frustration that waste imports continue to pose problems with wrongly or falsely declared waste shipments a frequent occurrence at ports.

Despite the high risks, the federal government has opted to allow the import of plastic waste under strict conditions.

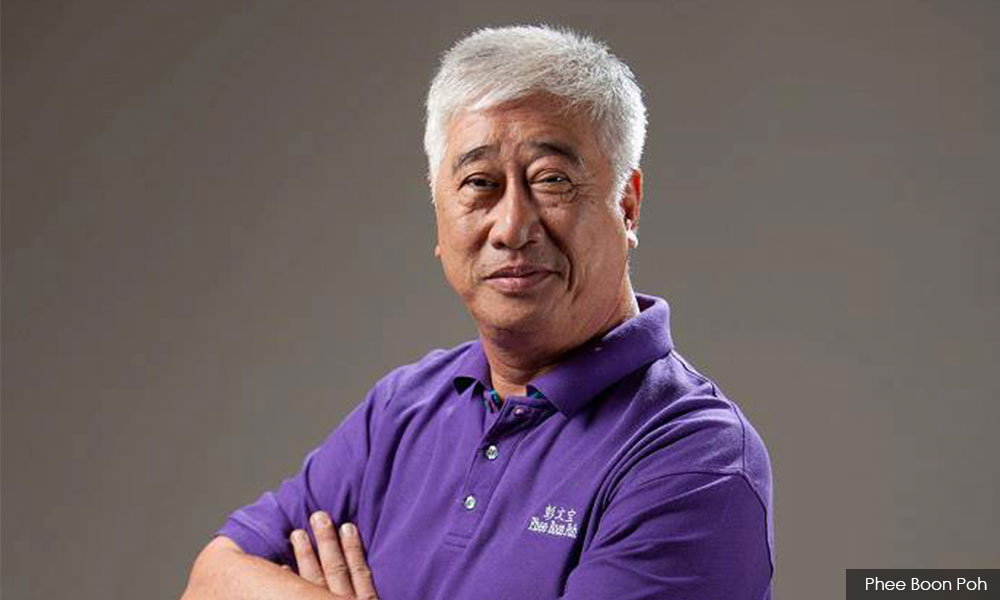

Nevertheless, Penang state executive council member for environment Phee Boon Poh lamented the lack of consultation with the state and local governments in the approval of import permits.

“You are coming into our house, there are house rules,” he said. “You cannot simply approve without consulting us.”

In 2018, Malaysia imported 872,531 tonnes of plastic scrap under the HS Code 3915. Due to strict enforcement and the crackdown on illegal activities, imports fell to 333,500 tonnes in 2019, but increased again to 478,092 tonnes in 2020.

Since January 2021, the trade of certain categories of plastic waste is subject to the Plastic Waste Amendments of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal.

Also, from June onwards, plastic waste importers in Malaysia must pay RM20 for every tonne of scrap brought into the country.

However, criminality and illegality in the global waste trade abound. Enforcement challenges include the lack of traceability of plastic waste, limited enforcement capacities, legal loopholes, and information gaps among enforcement agencies.

In recent months, plastic recycling factories have been caught violating environmental laws in Selangor - Rasa, Sungai Buloh, Puchong and twice in Telok Gong, 2020 and 2021 – as well as in Malacca, Johor Bahru, and Butterworth, Penang.

Local communities have also anxiously reported expanding waste recycling and pollution in their neighbourhoods for other scrap materials - non-ferrous metals, copper, paper, e-waste, and now tyres too, as seen in Telok Panglima Garang.

Corruption and pollution

Enforcement efforts can be severely hampered by a lack of integrity.

The National Anti-Corruption Plan 2019- 2023 (NACP) revealed that 23.9 percent of corruption complaints between 2013-2018 were related to enforcement, 8.6 percent were related to licensing and permits, and 1.2 percent related to business and industry, among others.

With the recent spate of cartel scandals, scams and dubious deals, one would be hard-pressed not to suspect irregularities in enforcement in Malaysia, which have emboldened illegal waste operators.

The Environment and Water Ministry launched the timely 2021-2025 Organisational Anti-Corruption Plan (OACP) last week, outlining 34 action plans encompassing financial management, governance and environmental management.

At the launch, MACC chief commissioner Azam Baki acknowledged that when it comes to environmental protection, a lack of integrity could threaten human survival.

In the face of a climate crisis, it is imperative that the government considers corruption and pollution risks when welcoming the global materials recovery and recycling industries.

Economic planning and development must incorporate future environmental risks, while laws regulating the generation, transportation, storage, treatment, and disposal of wastes should aim to minimise production, combat illegal dumping, and ensure disposal in an environmentally sound manner and as close to the source of waste generation as possible.

Equally important are measures to combat corruption, strengthen enforcement, and uphold the right to information and public participation.

There is a trust deficit in the country now. We need to rebuild trust and the best way to restore trust is through transparency. With transparency, comes accountability, competency, and integrity. - Mkini

The above is released by the Centre to Combat Corruption & Cronyism (C4 Centre)

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of MMKtT.

✍ Credit given to the original owner of this post : ☕ Malaysians Must Know the TRUTH

🌐 Hit This Link To Find Out More On Their Articles...🏄🏻♀️ Enjoy Surfing!

Post a Comment