Break misinformation chain to stave off state control of news portals

Politicians are well within their rights to hold journalists responsible for what they write. And journalists have the right to hold politicians accountable too.

Like a watchdog, journalists act as the people’s eyes and ears. They sound the alarm when politicians abuse their power.

But we were more like lapdogs during my years in the newsroom of typewriters and mini-cassette recorders. The Printing Presses and Publications Act and an array of security laws kept us in check. We generally toed the line.

Today, digital journalism has given journalists a longer leash to sniff out the political follies, incompetency and corruption. Some of what were dug out of the rabbit holes, media portals publish as evidence-based reports. Some as interpretive editorials; others as persuasive commentaries. And, a rare few, biting satire.

However, the line separating professional journalism from political spin is getting blurrier. Lately, contents hyper-critical of the government are treated as “fake”, a blanket descriptor that, according to a study of information disorder, denigrates journalists as professional communicators.

The simplistic application of “fake news” overlooks the differences between misinformation (unintentional mistakes, which sometimes occur in the short news cycle), disinformation (fabrication to support a popular rumour), and malinformation (deliberate falsification of context and contents designed to cause harm).

The Information Ministry’s blanket criminalisation of “berita palsu” (fake news) is a throwback to past state incursions into the work of critical online journalists and social media influencers.

While I reject the practice of making up news for personal gains by the likes of Washington Post reporter Janet Cooke’s bogus story in 1981 of a heroin addict, or her contemporaries Stephen Glass (The New Republic) and Jayson Blair (New York Times), the National Security Council’s directive is less about penalising the fabrication of falsehoods, malicious disinformation and racial and religious vilification.

The real issue is the arbitrary parameters of “berita palsu” that give the defence minister discretionary power to prosecute news portals for publishing materials that he feels are “untrue, inaccurate, and misleading”, which “can confuse the public and cause the rakyat to worry”.

Reason, logic and intellectual deduction of the nuances of information are thrown out the window.

Are we seeing a possible reinstatement of the Anti-Fake News Act, passed in May 2018 by former PM Najib Abdul Razak's administration but repealed by Pakatan Harapan last October by a 92-51 vote in the Dewan Rakyat?

Liberal organisations have rightly rung the alarm bells to prevent a return of the Act and keep at bay the ghosts of politically-motivated censorship. Past administrations have come down hard on unfettered political criticisms on the internet (Freedom House reports annually on the state of internet censorship in Malaysia).

The latest state incursion portends what a two-month-old backdoor government will do to suppress any threats to its fragile position following the abysmal performance of its ministers of health (warm water to kill Covid-19), higher education (Tik-Tok contest for students), housing and local government (public disinfection operation), and women and family (Doraemon and child marriage).

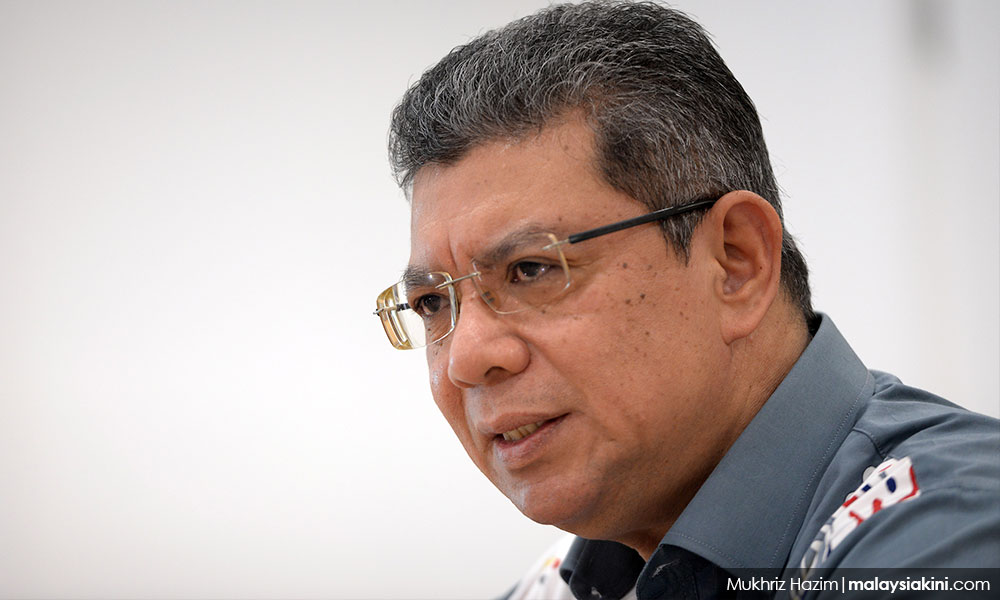

Saifuddin Abdullah (above), the minister of communications and multimedia, will need to live up to his credentials as a former CEO of Global Movement of Moderates, a proponent of academic freedom and a voice of reason.

The minister needs to ensure that the Perikatan Nasional government, tainted with the censorious streaks of Umno and PAS, will not interfere with the media portals’ watchdog surveillance of issues that matter to the people, particularly the 50 percent lower-income group most affected by Covid-19 and the movement control order.

The onus also falls on journalists to fact check their stories before publishing, and the rakyat to critically review what they have read and, often without thinking, share on social media. Failing which we will all unwittingly provide the agents of disinformation an open conduit to ply their conspiracies, and a reason for the state to come down hard on media portals.

Besides the Bahasa-only ‘fact-checker’ Sebenarnya.my on the MCMC website, users can follow some guidelines on how to break the chain of misinformation and disinformation:

- Always check the source of the original article, the writer’s credentials, institutional affiliation, and history of the site the article is published. Ask who is writing what to whom and for what purpose. Check the "About Us" link and the people managing the contents.

- Know the difference between news, editorial, satire and parody. Read in context because where the article is published often frames the intentions and meanings of the contents.

- Cross-check the reliability and authority of text, photos and videos that constantly show up in your social media. Algorithms from your search history and reading patterns tend to lead you down a spiral of materials – and advertisements - that align with your interests.

- Detect elements of confirmation bias – yours and the writer’s. We are more inclined to read what reinforces our opinions and claims to "truth". Google for evidence-based articles on what was reported for a deeper analysis.

- Resist the impulse to re-post before fact-checking what you have read. Break the news chain if you doubt the veracity of the information.

- Rely less on one major publication for your news. Diversify your sources of news sites from the political left to the centre-right, from the government and opposition, from the liberal to conservative.

- Balance your reading of brief updates of the pandemic with research-based articles from the World Health Organisation website.

- Question whether a photograph or a 30-second video clip sent to your device – some of which could be digitally altered and cloned – can really help you understand the larger issue. It usually is not.

- Take control of the news you read daily. Be your own truth-seeker by being more critical of what you read, view and share. If it is too good or dramatic to be true, it seldom is.

ERIC LOO is the founding editor of the academic journal Asia Pacific Media Educator. - Mkini

✍ Credit given to the original owner of this post : ☕ Malaysians Must Know the TRUTH

🌐 Hit This Link To Find Out More On Their Articles...🏄🏻♀️ Enjoy Surfing!

Post a Comment