Does Being Part Asian Make Me Less Asian?

Deep down, I still want to learn Cantonese. My grandfather, who emigrated to the Dominican Republic in the early 60s, came from China. He quickly rebuilt and rebranded himself, assimilating his status in DR as a friendly outsider. His son, my father, is a mix of Dominican and Chinese. My mother is Dominican almost entirely. In essence, I’m 25% Chinese; two generations from the mainland; idiomatically detached.

But my last name remains Sang and my face retains Asian features. And no matter where I go and who I encounter, that ends up meaning a lot. It colors the lens with which I am interpreted; Asian name, Asian face, Asian man. The reality that I speak Spanish, that I’ve lived in Santo Domingo, that I deeply care for and identify with the United States as my birth nation and home; those are mostly additional details. Amongst Dominicans, I am usually “el chino,” a term which I take as endearing if not a tad separatistic. My first school friends were Asian; we saw each other more easily than others saw us.

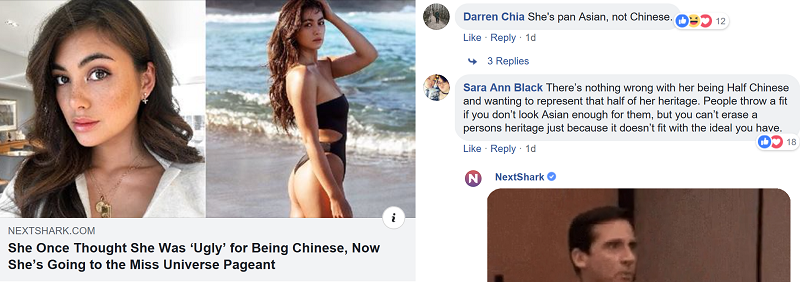

Yet as I grow in this Asian skin, this heritage which I love and understand to be essential my identity, I begin to feel a massive conflict. Now as a writer for NextShark, a platform by and for the global Asian community, I see comments about other biracial people; resentment over their transraciality, their unique and “un-Asian” physical attributes. I see what can be considered as downright hatred towards Asian women who date outside their race. And I understand the hurt. American society is programmed to disrespect Asian people; to fetishize Asian women and emasculate Asian men; to overlook our contributions and our oppressed state. And yet, classically, we as Asian people trap ourselves into only pushing for acceptance for our “purest” stories. We cast aside the complicated stories that don’t exactly fit the easy narrative.

Cynicism is healthy; destructiveness isn’t. Stories of biracial public figures learning to accept and appreciate their Asian heritage may raise eyebrows; if they are capitalizing off of newfound empowerment of their partial heritage, they are not the first. But we must not overlook the damage done to biracial people—the way they are nudged towards self hatred, towards a negative self image tainted by heritage seen as uncool or unwanted. We must not burn their candles at both ends simply because they have more than one end to burn.

Being biracial, at least for me, means being caught in between. You’re eager to understand both sides of an argument; to augment your inner dualities. You’d rather not swear allegiance to one extreme; you learn to balance things as much as possible. This is taught to you from your first moments of racial cognizance. As soon as you learn that every person you know belongs to a group—Filipino, Mexican, Croatian, Irish—you learn that you belong to several groups, and sometimes that feels like no group at all.

You also understand yourself to be the product of “race mixing,” a concept which in the 21st century you’d thought was outdated until realizing that it still very much engenders negativity. You realize that the concept you grew to believe, that you could date whoever you want as long as the person was right for you, comes with some baggage. You realize that even given your apparent 75% Dominican heritage, a percentage which should signify dominant features, you’re still subject to some of the same issues of Asian masculinity; you end up sifting through people who are attracted to you, wondering who genuinely takes interest in you and who you’re just a fetish to — a path through which one can get closer to their favorite K-Pop star.

You realize that your Asian masculinity, and all the complexity attached, leads you by nature to side-eye Asian women who “never date inside their race.” It takes a while for you to understand that these tend not to be decisions made from outright hatred, but machinations of a society that doesn’t find you attractive, that whitewashes your icons and your most powerful traits, leaving you the butt of a joke. You realize this causes internalized resentment; not only in Asian culture as a whole, but in the biracial children, like yourself, that have to deal with this dichotomy inside themselves. You realize how, in turn, this damns the Asian woman and her dating decisions, as she’s now essentially forced to choose Asian men or risk being harassed by Asian men who deem her a “race traitor.”

You begin to wonder, though you shouldn’t, about the opinions of others when you date outside your race. You wonder if your lover’s friends think she’s caught a case of “yellow fever,” or that she’s not satisfied sexually because you’re supposedly not well-endowed. You wonder if they don’t respect you as a male presence because you’re supposedly weak. You wonder if your lover’s family is championing you because you don’t pose a threat to their control, as a nice Asian boy; you wonder if they like you because you’re probably smart, probably good in school, probably well adjusted. You wonder if those seemingly positive outcomes resulting from prejudice really shake out to be so positive in the long run. These are not biracial fears; these are Asian fears.

Every biracial person’s experience is different: some biracial people can skate by on transraciality, possessing and perfecting their traditionally “non-Asian” features to reach a standard of attractiveness. As I grew up, my facial structure changed around a bit, and I began to experience this for myself. I went from being “one-hundred-percent, without-a-doubt Asian” to “Asian, but ethnically ambiguous.” And I love myself this way, just as I loved myself the way I was before. But the realities of my Asian name and features continue to be a part of my baggage; they color my world. Being biracial didn’t change being “el chino.” It didn’t change being told “to open my eyes” when I missed shots in basketball.

Race is an inexact science in that it’s not a science at all; it’s sorting. It’s a creation of colonizers, made to separate each group from each other through visual differences that, through propagandized training, appear more than skin deep. The truth is, the way you look is quite often the race you live as. The rapper Logic is half-white and half-black, and boasts he’s “not ashamed” to be either, that he’s “white as that Mona Lisa and just as Black as my cousin Keisha.” But he, most notably, carries white skin, white features, a typically white-sounding voice; so he lives as a white man. He’s treated as a white man. He’s identified with by white people. He’s not as likely to be pulled over by police when driving through a bad neighborhood. Say what you want about DNA; the way you look is the way you’re sorted, because that’s the principle of how “race” as a pseudoscientific categorization was created.

Therefore, I’m not an authority on whether or not Jhene Aiko can say the n-word. We are both very different looking biracial people with different experiences. What I do know is that those who claim their Asian heritage should be respected, no matter what other heritage that person shares. When biracial people accept their Asian heritage, we should accept their Asian heritage as well. When biracial people say they’ve felt ugly because of their Asian features, we should understand that to be a cruel side effect of oppressive social training, not some mark of an ignorant halfie. And if we do question mixed people, or people who give birth to mixed children, we should do so with patience, respect, and openmindedness; in other words, we should do much better than we have.

Feature Image via Instagram/jheneaiko, Instagram/Francesca.Jung, NextShark

The post Does Being Part Asian Make Me Less Asian? appeared first on NextShark.

✍ Source : ☕ NextShark

To continue reading click link or copy to web server. :

(✿◠‿◠)✌ Mukah Pages : 👍 Making Social Media Marketing Make Easy Through Internet Auto-Post System. Enjoy reading and don't forget to 👍 Like & 💕 Share!

Post a Comment